It is human nature to explore, to search, to push the envelope, and to expand our own limitations. Robert Peary in 1909 led the first team to the North Pole by dog sled; in 1914, Ernest Shackleton failed in his attempt to cross the Antarctic, but succeeded in rescuing his whole crew; Zachary Lansdowne and crew flew the first helium blimp 9000 miles back and forth across the continent, but were destroyed in a storm over Ohio in 1925; William Beebe in1934 invented the first submarine in which he reached depths of 3 028 feet;

It is human nature to explore, to search, to push the envelope, and to expand our own limitations. Robert Peary in 1909 led the first team to the North Pole by dog sled; in 1914, Ernest Shackleton failed in his attempt to cross the Antarctic, but succeeded in rescuing his whole crew; Zachary Lansdowne and crew flew the first helium blimp 9000 miles back and forth across the continent, but were destroyed in a storm over Ohio in 1925; William Beebe in1934 invented the first submarine in which he reached depths of 3 028 feet;Amelia Earhart was the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, but disappeared in 1937 attempting a solo mission around the world; Jon Turk, now 58 and wife Christine Seashore have led lives of adventure including the two year kayak trip from Japan to Alaska, peddle biking across Mongolia, and pioneering a new rout up Bolivia’s highest peak. This duo would now be leading our crew deep into the Andean mountains in search of first ski descents.

Although our journey was not as substantial as the aforementioned, the exploration gene had been passed down through the generations, leaving us unsatisfied with the normal pace of life, and sparking a match of curiosity for the road less travelled.

Although our journey was not as substantial as the aforementioned, the exploration gene had been passed down through the generations, leaving us unsatisfied with the normal pace of life, and sparking a match of curiosity for the road less travelled.The result of a conversation in February ’03 with Dave Fuller, regarding a ski mountaineering trip to Bolivia’s 20 000 foot mountains with other Fernieites Mark Cunnane, and ‘organised’ by Jon Turk and Christine Seashore, led me to the poorest country in South America with my luggage somewhere in Brazil. Awesome!

Fuller and I arrived three days after the rest of our group who was welcomed by Bolivia’s finest Banditos. As the trio was hiking out of the polluted valley of La Paz, they startled two men along the trail, who in return startled them with hand-guns and an appetite for some easy gringo coin. The average Bolivian income is around $1200 CDN, but this pay day amounted to over $1200 US cash, wedding rings, sun, corrective and field glasses, altimeter watches, and other ‘necessities’.

Fuller and I arrived three days after the rest of our group who was welcomed by Bolivia’s finest Banditos. As the trio was hiking out of the polluted valley of La Paz, they startled two men along the trail, who in return startled them with hand-guns and an appetite for some easy gringo coin. The average Bolivian income is around $1200 CDN, but this pay day amounted to over $1200 US cash, wedding rings, sun, corrective and field glasses, altimeter watches, and other ‘necessities’.Bolivia is comprised of 60 percent Quechua and Aymaria Natives, who often operate on the barter system but welcome both US dollars and Bolivianos, thus making our month long stay affordable – at least for Fuller and I.

Acclimatization to our new elevation of 14 000 feet was a necessity if we were to survive elevations over 20 000’. Following the ‘climb high - sleep low’ principle, we headed for the worlds highest ski area at 17 000’ where I was given old school skinny Dynastar skis and rear entry boots. I was psyched! As a kid skiing on Mt. Evergreen’s 300’ vertical, I always wanted the exact pair of skis I was now using; and who doesn’t like rear entry. The chalet was perched on a cliff overlooking the ski area. Inside we were served cocoa tea, as an employee attempted to get a fire started – easier said then done where the thin air barely fuels our bodies, never mind a fire. Outside, snow has started to fall as we descend the slope, and has quickly turned to a blizzard by the time we begin our ascent to the chalet.

Acclimatization to our new elevation of 14 000 feet was a necessity if we were to survive elevations over 20 000’. Following the ‘climb high - sleep low’ principle, we headed for the worlds highest ski area at 17 000’ where I was given old school skinny Dynastar skis and rear entry boots. I was psyched! As a kid skiing on Mt. Evergreen’s 300’ vertical, I always wanted the exact pair of skis I was now using; and who doesn’t like rear entry. The chalet was perched on a cliff overlooking the ski area. Inside we were served cocoa tea, as an employee attempted to get a fire started – easier said then done where the thin air barely fuels our bodies, never mind a fire. Outside, snow has started to fall as we descend the slope, and has quickly turned to a blizzard by the time we begin our ascent to the chalet.Bolivia’s wet season is from late summer to mid winter, and we are here May – June, which means the sketchy looking cable tow is inoperative; and this flash blizzard is unexpected. Probably safer to hike anyway - so we think. With skis strapped to packs we boot pack up the slope; meanwhile a buzzing sound grows louder in my ears, which I attribute to the altitude playing games with my head. A bolt of lightening, and the following silence proves my theory wrong. The buzzing sound soon returns to my skis/lightening rods attached to my pack, which are again silenced by another bolt of lightening. Crazy! I am overcome by a false sense of safety as I retire the borrowed equipment and hop into the bald-tired van for our descent of 2000’ of slippery switchbacks – much safer. We feel so safe that we hang off the back bumper and out the door, enabling a quick escape every time Victor locks up the brakes and slides into the 4” ridge that separates the single lane road from thin air.

Somewhat acclimatized, we head South West five hours of La Paz to Sajama National Park situated on the Chilean border; a trip that took Jon and climbing partner three days during his first visit thirty years prior. Climbing a new rout Mt. Sajama, Bolivia’s highest peak is just one short chapter in Jon’s adventurous book of life. Sajama was Bolivia’s first National park, which contains the alitplano (high plains) and its’ wildlife of three types of llamas and Andean ostriches (rheas). The large snow covered volcanoes of Pomerata and Parinacota shoot out of the planes and are silhouetted against a beautiful blue sky. This is our destination. At the end of the 4x4 ‘road’, we are greeted by a horse skull - fitting for this hostile environment, which serves us a round of altitude sickness. Somewhere above the maximum elevation of my altimeter watch (19680’), and below Parinacota’s 20 767’ summit our light fades and we retreat back to base camp. The next day, Fuller and I move our tent 1000’ lower to ease throbbing headaches, try to relearn our names, and hopefully regain an appetite worthy of more then four peanut butter dipped Fudgeos per day; meanwhile, Mark, Christine, and Jon take a rest day before conquering the volcano’s summit and peer into the 300’ crater before skiing down. Upon returning to the town of Sajama, we locate some hot springs and soak our bones as curious llamas graze nearby.

Somewhat acclimatized, we head South West five hours of La Paz to Sajama National Park situated on the Chilean border; a trip that took Jon and climbing partner three days during his first visit thirty years prior. Climbing a new rout Mt. Sajama, Bolivia’s highest peak is just one short chapter in Jon’s adventurous book of life. Sajama was Bolivia’s first National park, which contains the alitplano (high plains) and its’ wildlife of three types of llamas and Andean ostriches (rheas). The large snow covered volcanoes of Pomerata and Parinacota shoot out of the planes and are silhouetted against a beautiful blue sky. This is our destination. At the end of the 4x4 ‘road’, we are greeted by a horse skull - fitting for this hostile environment, which serves us a round of altitude sickness. Somewhere above the maximum elevation of my altimeter watch (19680’), and below Parinacota’s 20 767’ summit our light fades and we retreat back to base camp. The next day, Fuller and I move our tent 1000’ lower to ease throbbing headaches, try to relearn our names, and hopefully regain an appetite worthy of more then four peanut butter dipped Fudgeos per day; meanwhile, Mark, Christine, and Jon take a rest day before conquering the volcano’s summit and peer into the 300’ crater before skiing down. Upon returning to the town of Sajama, we locate some hot springs and soak our bones as curious llamas graze nearby. Retracing our steps, we arrive in La Paz to rest ourselves for a 14 hour, 400 km, over capacitated bus ride north to a town at the end of the road – Pelechuco. With two flat tires, scary switch backs, and rude Andean women, this is by far the craziest bus ride of my life – even compared to Grandma’s rally course to and from school during Kenora’s winter months. Pelechuco proves to be worth every minute of the cramped ride. Clouds from the Amazon drift into the 11000’ valley producing a vegetation of flowers, plants, grasses, and small trees. From the simple, stone village we hire six mules and two porters to haul our gear two days up the trail to the foot of the Apolobamba mountain range. Along the way we pass through another stone village that gives us the feeling we have stepped into a prehistoric fairy tale. Day two of our approach begins by the four-hour search for the mules that were left to roam and graze.

Retracing our steps, we arrive in La Paz to rest ourselves for a 14 hour, 400 km, over capacitated bus ride north to a town at the end of the road – Pelechuco. With two flat tires, scary switch backs, and rude Andean women, this is by far the craziest bus ride of my life – even compared to Grandma’s rally course to and from school during Kenora’s winter months. Pelechuco proves to be worth every minute of the cramped ride. Clouds from the Amazon drift into the 11000’ valley producing a vegetation of flowers, plants, grasses, and small trees. From the simple, stone village we hire six mules and two porters to haul our gear two days up the trail to the foot of the Apolobamba mountain range. Along the way we pass through another stone village that gives us the feeling we have stepped into a prehistoric fairy tale. Day two of our approach begins by the four-hour search for the mules that were left to roam and graze.Once on the trail, our porter asks what our long boards are for, confirming our assumption of us being the only skiers to the area. After some charades and bad Spanish, Remi smiles in satisfaction to our explanation. The valley ends at the foot of an astonishing glacier where we set up base camp, and ask Remi to return the following week. This request is a gamble, as Bolivians are known for their lack of understanding or concern for time. The Lonely Planet suggests that a Bolivian, when invited for lunch, might show up two days late and not think anything of it.

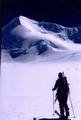

The days to follow consist of 5:30 alarms to give us appropriate time to hike past the heard of wild horses, skin up and across the glacier to our chosen peak, strap on crampons to summit, take in the breathtaking views, and ski first descents back down to the glacier; trying not to fall as each line ends in a crevasse or burgschrund. Ascarani, a 55 degree, icy peak is my first descent, followed by Katantika, and lastly Miradar. At one end of the glacier, Bolivians have built a gold mining camp that entertains us with periodic dynamite blasts. The extracted gold is then backpacked out to a road and transported for sales or trade – talk about a hardy breed.

Our days of skiing and intermission rest days come to an end two days after I have finished my last meal of Ichi-Ban – apparently I have recovered from altitude sickness and have regained my appetite. Although here for only a week, the simplicity of our days feels like we have been here a month, and I gain an understanding of how time becomes irrelevant. Remi shows up half a day late with his mules to pack us back to Pelechuco, where we gorge on my new favourite meal of bread and peaches smothered in sweet and condensed milk; we then move onto the main course, which I eat until I am literally sick and must excuse myself to el bano.

Fuller and Cunnane cut the trip short to attend to business back in Fernie, while Jon, Christine and I embark on another epic adventure; a four-day hike east out of the Andes. The plethora of mining roads combined with inaccurate maps leads us astray, and we spend three days retracing our steps, crossing wrong passes and searching for a town that we doubt exists. At one point along some dead end road, Jon turns and says, “I kinda like being in some strange country where I have no idea of where the Hell I am”. This statement sums up Jon’s approach to life – it is not about the destination, but rather the adventures along the road. Eventually we arrive at our destination, but not before a stray dog adopts us as his owner and spends two days following us begging for food, and barking at cows, people, and anything else that comes our way.

Our mission of: go to some foreign country with really high mountains, find a way to the top, and ski down, was now complete. Another exploration to satisfy those curiosity bones had come and gone. I returned to La Paz for a night of puking from some food poisoning before hopping a plane back to Canada where I was cheerfully greeted by an upstanding Canadian citizen who’s English was worse then my Spanish. Now back in the comforts of this unreal world, I have become anxious by routine governed days, and thoughts of other ski/travel adventures flood my cramped brain. The next adventure lies just around the corner.